Callie Hill’s yearning to learn the Mohawk language first began when she became a mother.

Before that she had only had cursory interaction with the language, which had faded out of common use in her family during her grandparent’s generation. She refers to Mohawk as her first language; she, like other Aboriginal peoples, considers her first-tongue to be her Aboriginal language.

“My grandparents were of the generation that spoke the language so that their children and grandchildren wouldn’t understand what they were saying,” Hill explains.

When she was a child her father would use Mohawk words, through Hill wouldn’t be able to recognize the words as being Mohawk until she was an adult.

“I just knew that the words he was saying meant ‘hurry up,’ for example, but for the longest time I didn’t know that it was Mohawk,” she says.

Now, as director of Tsi Tynnoheht Onkwawenna, an organization that provides language and culture programming in the Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory, Hill has developed a much broader understanding of the Mohawk language.

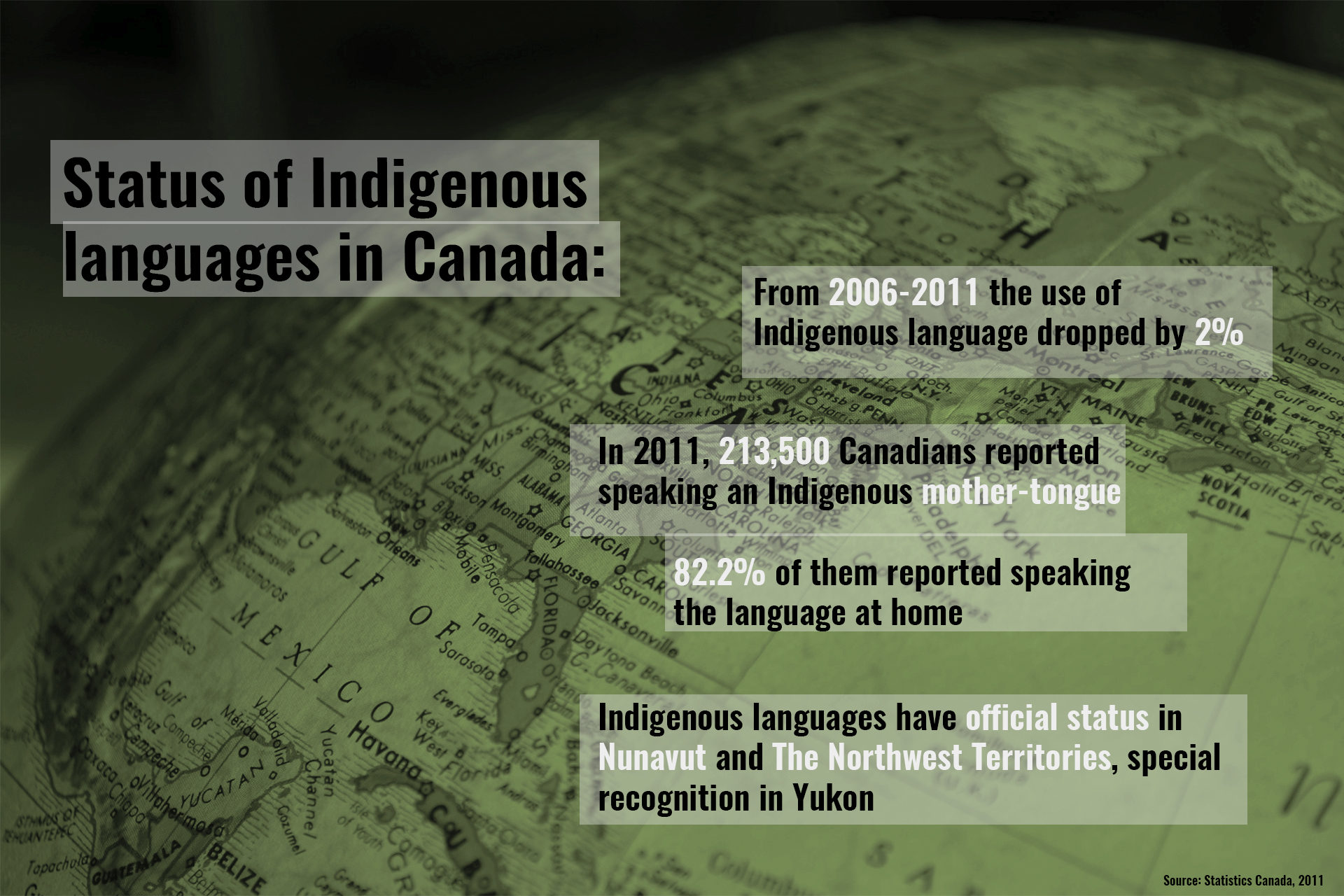

Hill’s story is not uncommon in Aboriginal communities. According to Statistics Canada, the Indigenous language use declined by two percent between 2006 and 2011, while the Aboriginal population in Canada grew by 20 per cent.

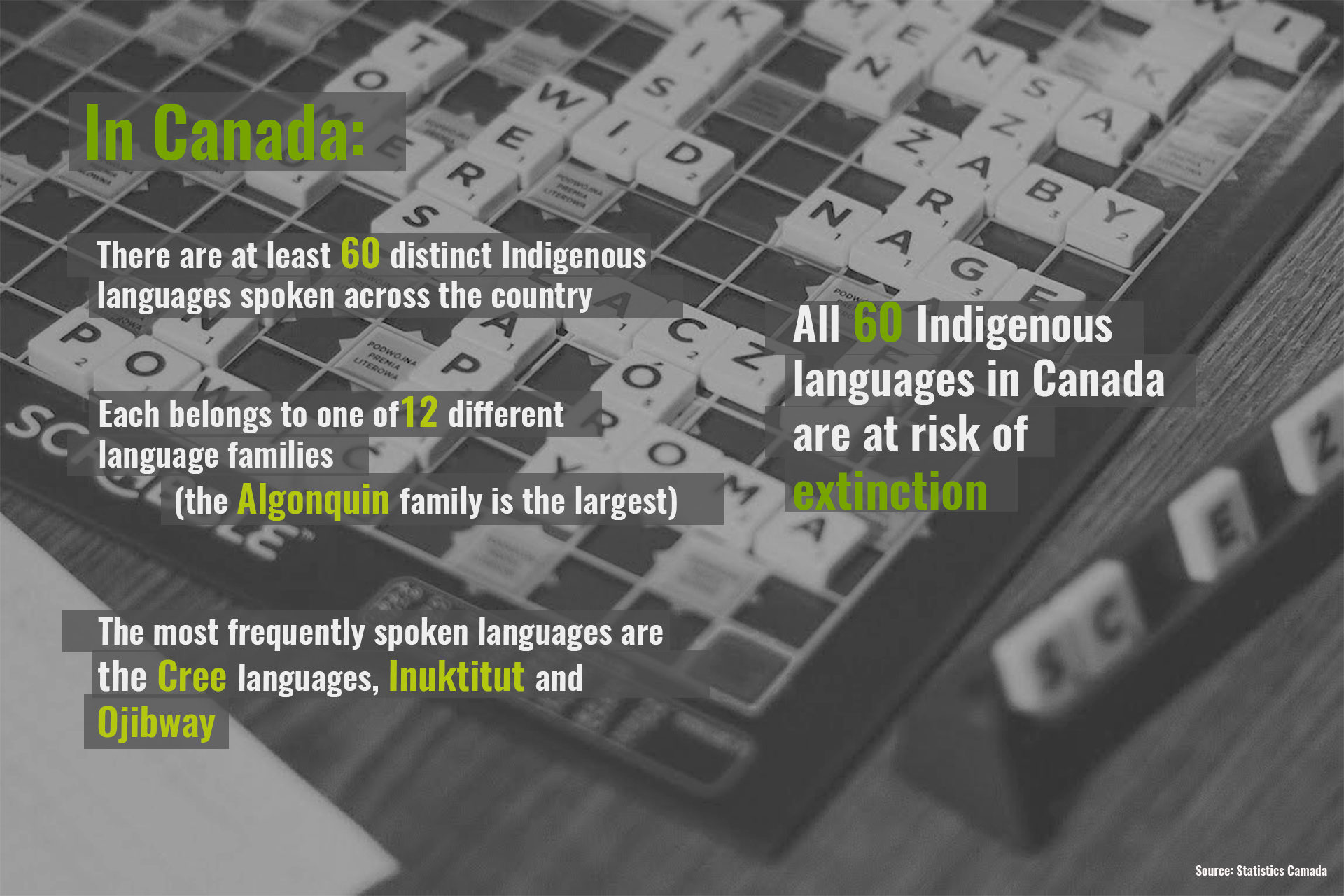

The use of and proficiency in Indigenous languages has been on a steady decline for decades. Statistics Canada reports 60 Indigenous languages in Canada, though other sources present a range between 58 and 75. All are at risk of extinction.

The loss of Aboriginal language intertwines with a complicated history of the treatment of Aboriginal peoples in Canada. Language knowledge and use intersects heavily with racism, prejudice and the legacy of the residential school systems in Canada. The historical marginalization and mistreatment of Aboriginal communities created emotional, mental and physical barriers to language use. Children were advised by parents not to speak in their native tongues or to use their Aboriginal names. In residential schools, children were systematically kept from using their first languages to forget their first languages; they were often reprimanded with physical violence if they disobeyed. Often, language retention became impossible or, at the very least, incredibly uncomfortable.

The legacy of this mistreatment created a generational gap in language knowledge. In this gap, language proficiency was lost—often because parents were hesitant to teach a language that they worried could negatively affect their children. In many instances, the language no longer existed to be taught.

Candace Maracle, a filmmaker and freelance journalist from Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory, knows the impact of these wounds too well.

“My grandparents would have spoken their language, but it was gone,” she says. “It was beaten out of them.”

When Maracle’s mother spoke Ojibwe to her as a child, she did it with reservations.

“She used it as though it was a forbidden thing,” Maracle says. “I think there was still that part of her that was ashamed of being First Nations, she would say ‘This is your Indian name,’ but she was cagey about it— she told us not to share our names with anyone.”

Now, Maracle studies Kenien’keha, an endangered Indigenous language. The knowledge of the language has allowed her to become closer to her cultural roots.

It is not all that uncommon for a language to fall into disuse or extinction and often languages change as part of a natural evolution. When a language naturally falls out of disuse, the loss is more palatable. Generally, it is part of a natural evolution— when a language loses its usefulness it begins to disappear. But, as Callie Hill explains, the loss of Indigenous language is a more profound, culturally gouging experience.

“It’s so hard to explain, our language is so descriptive and so deep. Our culture is right in our language,” she says.

She uses the word mother as an example, attempting to put into words some of the complexities of what, in English, seems to be a simple term.

“Mother has a possessive pronominal,” Hill says. “We own our mothers and our mothers own us, but it’s different for father.” This complexity, she explains, is directly related to the term’s cultural significance in her language and it’s relationship to their matrilineal society.

Connie Hartviksen, program manager at Mishko Bimaadziwin Family Support Services in Thunder Bay, Ont., unpacks the term even further.

She explains that in the Ojibwe language, speakers say Maamaa to refer to mother, regardless of context. ‘My mother’ is Nimaamaa and ‘Mother Earth’ is Maamaa aki.

“Aboriginal language is so different than the English language,” Hartviksen says. “It’s a very descriptive language and there words in the language that keep us connected to the world we live in, to Mother Earth, to culture that can’t be described in any other language,” she explains.

For Hartviksen, the influence of language is multifaceted, and contributes to a greater sense of health and well-being and, perhaps most importantly, a greater connection to Aboriginal culture and cultural practices.

At Mishko Bimaadziwim, she works a great deal with adults for whom secondary language acquisition is far more complicated. The organization’s goal is, in part, to encourage parents to develop an understanding of the Ojibwe language so that they are able to support their children’s language development at home.

“It’s a lot of work for the adults, they really have to want the language,” Hartviksen explains. “Younger parents may have a sense of shame and frustration, certainly I’ve heard instances where young people are trying to get their language back, but the fluent speakers are fairly critical of them for not saying things right.”

Children can be the spark for repairing the generational gap, says Hartviksen. In her community, she explains, parents often feel the need to learn the language in order to communicate with their children, many of whom spend the entire school day speaking Ojibwe.

This was certainly the case for Hill, whose experience as a mother and now a grandmother ignited her desire to reconnect with the Mohawk language she had never known.

“It goes back to the idea of how we are all connected as a community,” Hill explains. “It’s my sense of family that has made me realize how important that is.”

Language revitalization efforts, however, do not come without challenges. Hill estimates that there are only 50 to 60 fluent speakers in the community, none of whom are over the age of 40. Currently, one family within the community is raising their children with the language; according to Hill their five-year-old daughter was considered the most proficient speaker on the reserve for some time.

Funding and finding fluent speakers to teach are the biggest challenges Hill has experienced in facilitating language revitalization efforts within her community since the efforts first took hold 12 years ago. Despite the obstacles to the process, she is optimistic.

“We need this in our community as well so that people understand that if they aren’t doing something to regenerate our language then they are allowing it to die away,” Hill says. “I don’t know how many of those people understand the depth of the loss that we will feel if we let our language go.”

Hartviksen has found similar obstacles in language revitalization efforts within the communities she has worked with. Success, she stresses, is largely dependent on community motivation.

“Some communities have long lost their languages and their focuses are on other things, others are so gung ho that we can hardly keep up with them,” she says. For Hartviksen, the key is encouragement and reducing the roadblocks that discourage people, particularly adults, from the already complicated process of learning another language.

“When you’re faced with embarrassment you tend to stop,” she says.

Despite the obstacles, there optimism that, through community-based revitalization efforts, Indigenous languages will flourish once more.

“I’m an optimist—I believe I should be looking in the direction I want to go. I’m seeing a confluence of revitalization efforts within the community,” says Maracle.

Though tenuous, revitalization has begun to grow language proficiency among both Aboriginal and non-Indigenous participants in communities working diligently to encourage it revitalization’s growth.

“You can look at the act of settlers learning the language as an act of Reconciliation— to even superficially feel the connection to a language,” says Hill. “I’m all about planting seeds with people.”

For Hartviksen, the knowledge of an Indigenous language is an empowering experience for all involved. “In our organization there are almost as many non-Indigenous as Aboriginal participants. It’s important, it’s respectful and it builds community.”

She adds, “You don’t learn unless you ask.”